For the ancients, the u n i v e r s e was understood to be made up of four archetypal forces or elements (earth, air, water, and fire) so formalized by Empedocles (450 BC) – the TETRASOMIA –

In the human body, these substances came to correspond to the cold, the dry, the moist, and the hot bodily fluids. In their contrary actions, they maintain the harmony and the equilibrium of the mundane machinery of the organism and seem to be the result of a universal human mental image of the matter that makes up the body. These four elements were animated through the interaction of two great living energies: Eros and Eris. Eros was magnetic attraction and Eris was the name given to competitive antagonism.

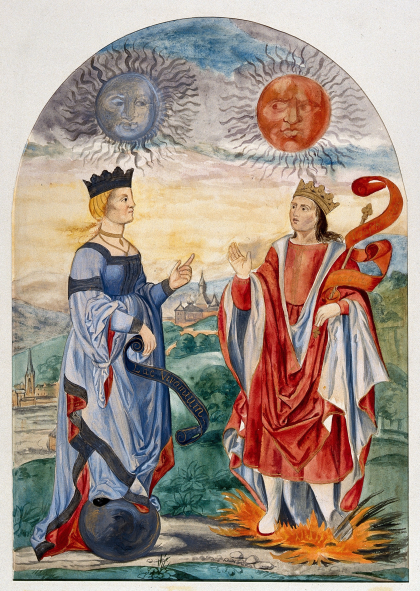

The Egyptians represented the moon, an emblem of the power of feminine attraction, and used the sun to symbolize the strength of masculine antagonism.

Later European Alchemy represented this magnetic feminine energy as the ‘Queen’ and the warlike masculine energy as the ‘King’.

Natural Philosophy, the science of the time, could then be read in the symbolism of the alchemical process of dissolution and recomposition – solve et coagula – how these fighting opposites ultimately can join the four elements in loving union, and so spiritually elevate the fundamental composition of all living matter.

Wet and dry primary qualities represent fluidity, flexibility, or rigidity that which allows a thing to define its shape and bounds. Wet things are volatile and expansive, they fill the spaces in their surroundings; dry things, on the contrary, are fixed and structured, they define their form.

Sun and moon, male and female, fixed and volatile, cold and hot, moist and dry could, through extraordinary human effort, be transformed into what was called ‘Philosophical Mercury’ (a metaphysical substance that achieved the conscious expression and coexistence of the opposites within the unity of the human soul), so crowning man’s psychological process of discovery and individuation. This unity of the ‘Prima Materia’ could only be reached by separating its unconscious parts, by dissolving and purging their impurities, to then proceed to a new coagulation at a consciously higher level of spiritual purity.

The Greek physician Hippocrates (460-370BC) is believed to have developed a proto – psychological theory of the four temperaments, and Galen (129 -200 AD) to have named them after the bodily humours: the theory continued to be adopted by Greek, Roman, and Islamic physicians – all emphasizing the link between the psychological and the physical processes of health and medicine.

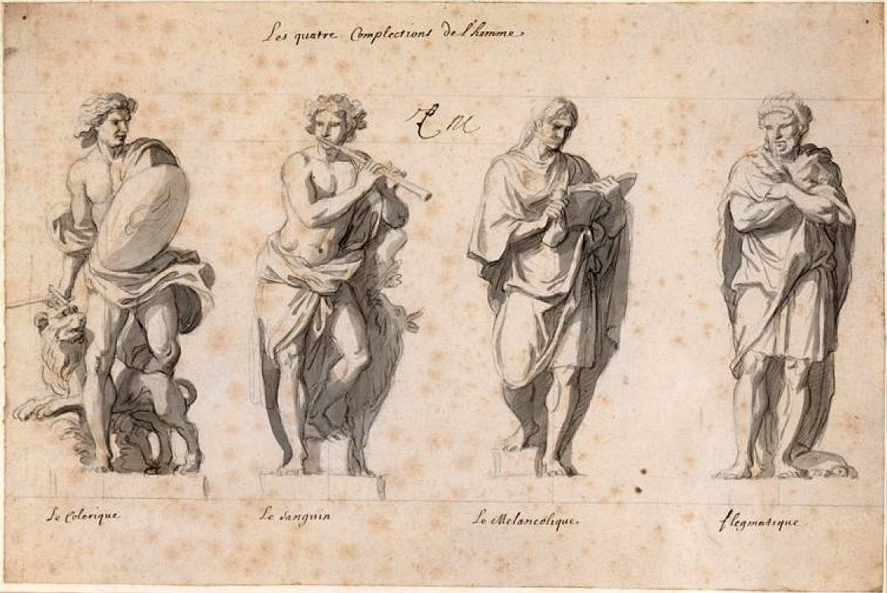

Blood was hot and moist, phlegm was cold and moist, yellow bile was hot and dry while black bile was cold and dry. These humours approached some form of equilibrium in the healthy man but they also emblematically described, in their imbalance, his psychology, his personality – the Sanguine, the Phlegmatic, the Choleric, and the Melancholic type of human being.

Blood was associated with the ‘sanguine’, and the heart distributing air and oxygen through the tissues of the body; a man who was extrovert, sociable and changeable, hot and wet. Yellow bile, to be found in the spleen, a by-product of digestion and energy transformation made the individual ‘choleric’, hot and dry, energetic, ambitious, and enthusiastic. Black bile, in the liver or the gall bladder brought about a ‘melancholic’ force that was cool and dry – a person who tended to be sluggish, rigid, and practical, of an introspective disposition, while the ‘phlegmatic’ was cold and wet, in touch with their feelings. The water element is associated understandably with dissolution, diffusion, and flow, flexibly adapting the individual towards emotional harmony.

The philosophers and physicians of the Elizabethan era, Robert Fludd and William Harvey, William Paddy, and Richard Andrews, while employing much standard Galenic Medicine, also inspired the Royal College of Physicians to think about a new theory of illness: how quintessential Air and light, which through the breath and the body’s pores also brings disease, can alter the delicate balance of a fourfold vital force hidden within the innate heat and metabolism of the blood itself.

The essence of blood is exchange and contact, it is movement and circulation … and, ultimately reveals the layered traces of all four humours: for the Elizabethans found (as we can today) the ‘Sanguine’ humour in red haemoglobin, the ‘Phlegmatic humour’ in the clear plasma, the yellowish ‘Choleric’ humor in the residue or bilirubin, and ‘Melancholic’ humour in the dark brownish sediment with the platelets and clotting factors. Thus we have haematoscopy, an inspection of a flask of blood, in a similar way to the inspection of urine in a flask (uroscopy) with which we are more familiar. Since bleeding was a popular treatment method for many ailments, there would not have been a shortage of this important diagnostic fluid.

However, the Elizabethan understanding of the world was above all profoundly symbolic, and their metaphorical analysis of the cosmos as it expressed itself in the human body was not naïf. In their search for knowledge, they looked for harmony in the multiple levels of physical and metaphysical existence, and in the correlations and communication between all the layers of living substances. They understood the microcosm – man – as an integrated part, even a reflection of the macrocosm; as the sun is to the earth, so the heart is to the human organism. So they studied astrology, the influence of the planets around the sun, the circulation of their orbits, the circulation of the blood, and the symbolic attributes of such celestial bodies in the different aspects of human organs. The gravitational pull of those values attributed to the Moon was seen as its ‘phlegmatic’ (watery) influence, or in the red planet Mars as ‘choleric’ (fire, and feverish) strength, in Saturn, a ‘melancholic’ (earth-weighty) disposition.

The culture of the time – above all with Shakespeare – used the terminology of these astrological processes and imagery and applied the concepts to the inner mental workings of the characters described on stage. It seems that Shakespeare choreographed his players’ moves in so much as they should stand beneath the influence of Mars, as depicted in the constellation on the ceiling above his theatre, the Globe, if engaged in warlike representation, or under the astrological patterns of Venus, absorbing her celestial rays, when invoking enchantment and seduction:

‘But, soft! What light in yonder window breaks? It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.

Arise, fair sun and kill the envious moon,

Who is already sick and pale with grief,

That though her maid art far more fair than she’.

(Romeo 2.2.4-8)

Each actor would find their place of power on the stage and perform, so manipulating the cosmic energies and consciously embodying for the public the shadows of the unbalanced humours. In fact, throughout Shakespeare’s many plays his basic theoretical scaffold of the human character reveals the depths and complexities of these ‘humours’, and through his cathartic theatrical work he tries constantly to integrate them, into the service of a healing balance. Different parts of the body, attacked as they were by illness, analogically, were traditionally subject to the astrological constellation of the stars and the movement of the forces and the elements that made up the Universe.

‘ … as yet thou art my flesh, my blood,

my daughter or rather a disease that’s in my flesh which I must needs call mine;

thou art a boil a plague sore,

an embossed carbuncle in my corrupted blood’.

(King Lear 2.4.242)

The old man (in the Winter of life) weighed down by Earth and Melancholy, is influenced by the planet Saturn and the metal lead. He unbalances into insanity as the image of the daughter he once loved twists and deforms into disease … in his mind. Ultimately this corrupts his ‘blood’ – his Sanguine, joyful Spring of Life.

Hippocrates was still teaching the Elizabethans that:

‘When all these elements are truly balanced and mingled, man feels the most perfect health. Illness

occurs when one of these qualities is in excess or is lessened in amount or is entirely thrown out of

the body’.

(Hippocrates, The Constitution of Man –

Part IV)

So sometimes it was a question of bringing the unrecognized shadow of the ‘humour’, the disowned malady, back within the confines of our healing powers, into integration, a question of accepting the unconscious projection, as Prospero admits in The Tempest:

“This thing of darkness (Caliban) I acknowledge mine”

…or, on a lighter tone, Toby Belch in Twelfth Night a phlegmatic character who performs exorcism on the ‘possessed’ Malvolio (he of bad will ) so that he may bring pleasure back into the world, and so reestablish in a more Sanguine atmosphere, greater good will!

Ultimately, it is perhaps Ophelia who best represents her life and her death, a conflict of the humours. No alchemical ‘coniunctio oppositorum‘ can be reached by this creature who longs still to belong most dutifully to the pure and virginal world of her Melancholic father, and yet also dreams of belonging to Choleric Hamlet who requires her sexuality yet disdains her love. Slowly she becomes possessed by their humours, by the conflicting passions of these men, who believe in some way that they own her and must control her. The images of their conflict in her mental existence overwhelms her inner Phlegmatic personality and, powerless, in bondage to obedience, she can only sink into the ever deeper dark waters of oblivion… to drown therein.

May she, perhaps, await with the flowers of remembrance and rue, her own alchemical rebirth?

We are still touched by the power of Shakespeare’s characters who illustrate our social and psychological ill health, and our lack of equilibrium. They are case histories that incarnate the shadows of hallucination, paranoia, nervous disorders, and various imbalances of the humours in the human organism. His personality types transport us into their life stories to share their changing seasons, their moving days and dispositions… and marvelously illustrate for us still today, the four humours of old.

‘Tetrasomia‘ continues to exist, for we may well encounter a similar attitude in many of the Indigenous forms of medicine around the world; in the Indian Ayurvedic approach or the Chinese and Tibetan traditional forms of healing, among the Shamans of Mexico and the Curanderos of South America, even among the traditional medical practices of the Celtic nations. In various branches of modern medicine too we find an understanding of living elemental life movement and we revert to seeking the building blocks of our very existence.

Finally, it is in psychotherapy and psychiatry that these constitutional character types truly continue to distinguish themselves in behavioral theories and psychoanalytical personality tests.